Leading retailers know that how you sell is just as important as what you sell.

Their merchandising strategies can be easily applied to your sales content. By using these tactics to build dynamic seller experiences, you can deepen rep engagement with your enablement platform and boost the consumption of critical sales content. Let’s take a closer look at how.

Curate Your Display

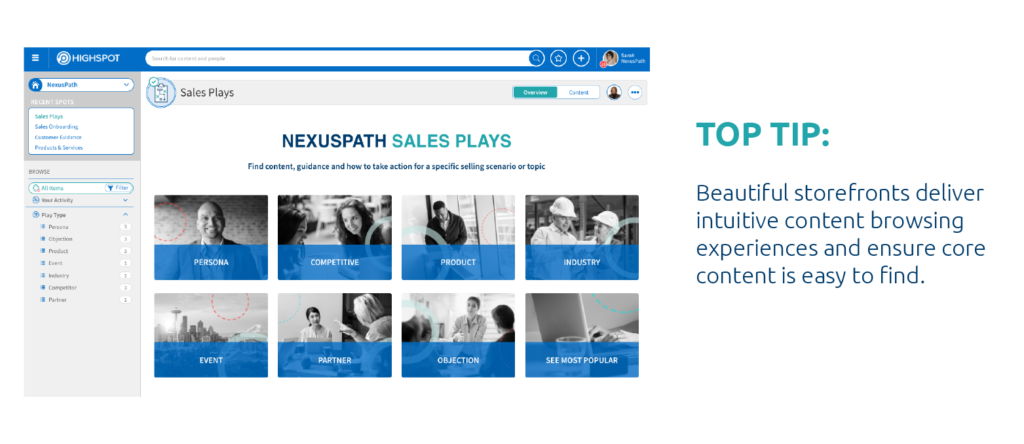

Whether it’s an eye-catching window display on Fifth Avenue or a sleek website, retailers know that presentation is critical to keeping shoppers coming back for more. Enablement is no different: Your enablement platform is your storefront — and a beautiful, curated content display will help you capture and keep rep attention.

One surefire way to do this is by building dynamic landing pages or content overviews. Rather than overwhelming salespeople with a deluge of sales assets, these “guided experiences” let sellers quickly digest information and navigate to what they need.

To build an impactful landing page, put yourself in a seller’s shoes. How would a rep want to navigate content? Likely it will be by customer industry, persona, or deal-size — not content type. Further enrich your landing page with interactive elements, whether it’s content carousels, multimedia displays, or quick links to popular assets.

Creating organised, curated landing pages and content overviews ensures the right assets are front and center and packaged in a user-friendly browsing experience that reps will love.

Cross-sell Your Content

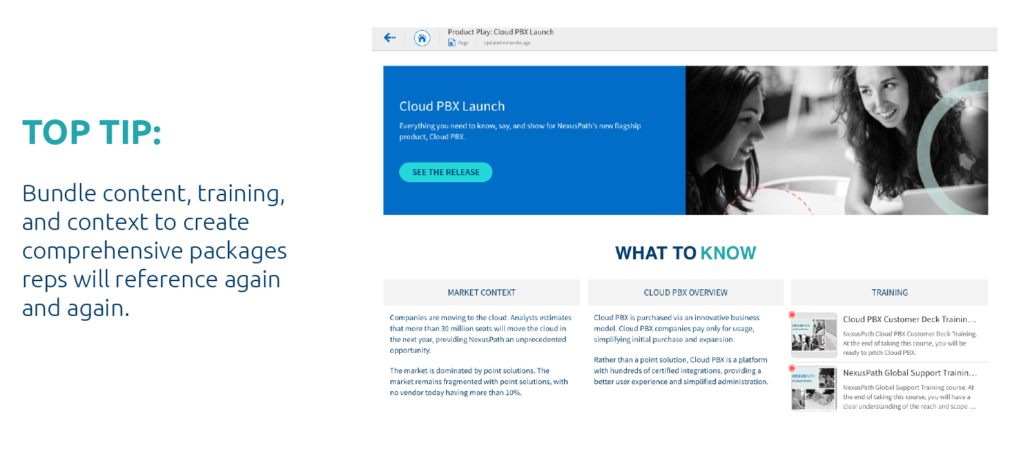

Product displays often feature relevant items side by side, like jars of spaghetti sauce next to boxes of pasta. This simple strategy ensures that shoppers leave satisfied with full carts. For enablement professionals, cross-selling your content is an easy way to boost engagement across multiple assets.

Consider how you launch new content — rather than simply uploading a new whitepaper or datasheet and hoping reps discover it, try packaging related assets together. These content kits are a fast way to create value for sellers and deepen content engagement. Instead of searching for the perfect blog to send alongside a new whitepaper, reps will be able to quickly find, consume, and distribute relevant assets.

Bundling training content is also an effective way to improve engagement and retention. Say you’ve recently launched a new product offering — including a kit of required reading within a sales play is an easy way to get eyes on essential training assets.

By working these tactics into your sales enablement strategy, you’ll make it easier than ever for reps to consume the critical content they need to succeed.

Use FOMO to Your Advantage

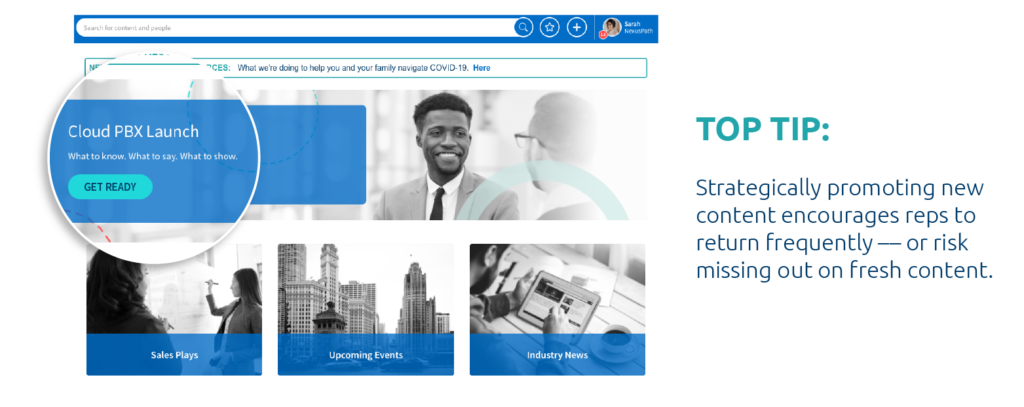

Fast fashion retailers are famous for their ever-rotating product displays and changing store layouts. But this shifting inventory is intentional — it tells shoppers that if they don’t check back regularly, they may miss out on a great deal.

Enablement professionals can also use the fear of missing out to create a sense of urgency. By regularly promoting new assets, you can signal to reps that if they don’t visit your platform frequently, they risk missing out on deal-winning content. Eventually, checking for new content will become a habitual part of your rep’s daily workflow.

To put this strategy into play, use interactive widgets to create bold promotional displays on key landing pages within your sales enablement platform, like the example above. You might also consider communication channels like Slack or email to share announcements. Finally, think about the materials you want sellers to visit more often — perhaps it’s a key sales play or a new training module. Refreshing featured assets on these landing pages gives reps a reason to return again and again, thereby ensuring continued engagement with key materials.

Mixing up your promoted content is a low-effort, high-impact way to and remind reps to check your sales enablement platform frequently — and consume more materials along the way.

Organise Assets to Tell a Story

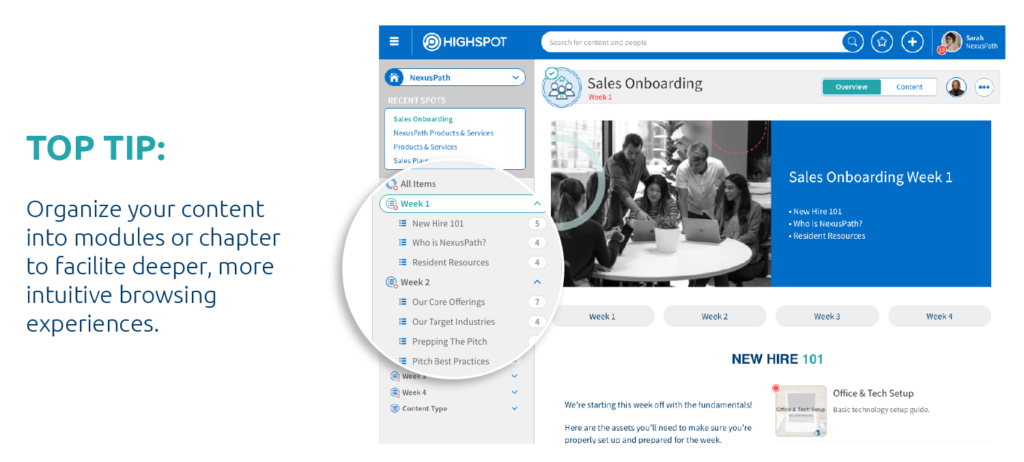

To the untrained eye, store layouts may seem random; in reality, they are meticulously planned to ensure maximum exposure to products. Enablement professionals can borrow this line of thinking.

Rather than surfacing content en masse, think about how you can contextualise assets with “chapters” or “themes” to create a narrative arc that goes beyond simple categories like region, industry, or persona. For example, content meant to be distributed to buyers might be organised into best bets by buyer stage. This helps sellers know when to use certain assets and encourages them to return to your enablement platform again and again over the course of a sales cycle in order to find the next piece of recommended content.

This approach works for internal sales content like onboarding and training materials as well. Internal content often comes in packages of numerous detailed documents. But by organising assets into stories, they become bite-sized and much easier to browse and consume. A rep can simply find the materials they need, consume them, and return for the next module when their deal demands it.

Thoughtful organisation of sales content boosts exposure to key assets and simplifies how sellers interact with your platform.

Merchandise Your Way to Higher Content Engagement

Bringing a little bit (or a lot!) of merchandising strategy to your sales content management can have a big impact on your team’s experience — and your bottom line. By making your sales enablement platform as intuitive as possible, you’re sure to keep reps engaged and up-to-date with high-impact content.

Ready to revamp your sales asset management strategy? Get started with new content management best practices from Forrester | SiriusDecisions.