We’ve all had to make significant changes in response to the global pandemic, and sales teams are no exception. As the global economy was upended, the pandemic forced a shift to both virtual selling and virtual sales training. Some companies floundered while others flourished.

Sales teams that were able to adapt to life during COVID-19 showed their resilience. Those teams helped their companies to excel and have a banner sales year despite the challenges they faced. Meanwhile, other companies fumbled and reported low or negative growth.

To explore how remote salesforces were able to navigate a global crisis, ValueSelling Associates and Training Industry, Inc. surveyed 256 sales leaders and learning and development (L&D) decision-makers about the approach their companies are taking toward developing sales skills and managing change. Did sales training have an impact?

As may be expected, the survey found that the high-growth companies were the ones that could see the need for change early and pivot accordingly. For example, almost half of high-growth companies focus on upskilling their salespeople in presenting virtually, while only 13% of negative-growth companies do so. This type of investment pays off in spades, especially when reps must sell in a remote environment to maintain revenue growth.

One of the most notable findings was that soft skills matter, especially when companies encounter market uncertainty and rapidly shifting business needs. As we dug into the research data, two distinct groups of companies emerged — high-growth companies that reported 2020 as a banner year and negative-growth companies that marked 2020 as the worst of the last five years.

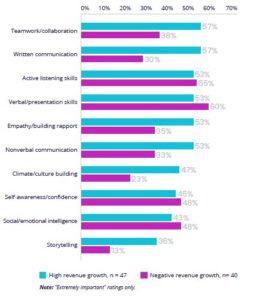

Although soft skills are always essential in sales, when business requirements are rapidly shifting, they make even more of a difference. Think for a moment about a business transaction you’ve had recently. Perhaps you were more tentative. In such cases, you long for an empathetic salesperson who truly listens and “gets” you. We compared the skills of top performers at high-growth companies to those at negative-growth companies. Here is where the most significant differences between the two groups were evident.

- Written communication

- Climate building/culture

- Storytelling

- Non-verbal communication

- Teamwork/collaboration

The following chart gives a complete look at how the high-growth companies fared versus the negative-growth companies.

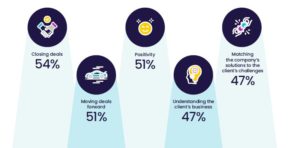

Soft skills reinforce and boost the critical sales skills that are important in any customer interaction. It is important to note that high-growth companies take a multilayered approach, skills, and change readiness strategy. Instead of a magic bullet, it comes down to a constellation of factors. Sales professionals need relevant and up-to-date skills to succeed, and our respondent data showed that companies have focused on the following essential sales skills to succeed:

So, what differentiates companies that grew in 2020? High-growth companies share some of the same priorities listed above, such as closing and moving deals forward. However, they are also focused more on prospecting, negotiating, differentiating from the competition, empathy — and, notably, presenting in virtual settings.

Across the board, high-growth companies were the ones that could see the need for change and pivot accordingly. Notably, sales training plays a more prominent role in all outcomes in high-growth companies than in negative-growth companies, especially in agility or the organization’s ability to manage and adapt to change quickly. Resilience has become the buzzword of the pandemic, and rightly so. Resilient sales professionals who develop and use their soft skills are more likely to come out as winners.

For more detail on the survey results, download the ValueSelling Associates report, “How High-growth Sales Organisations Respond to Crisis.”