Grow Your

Career at

Highspot

Regarder la vidéo

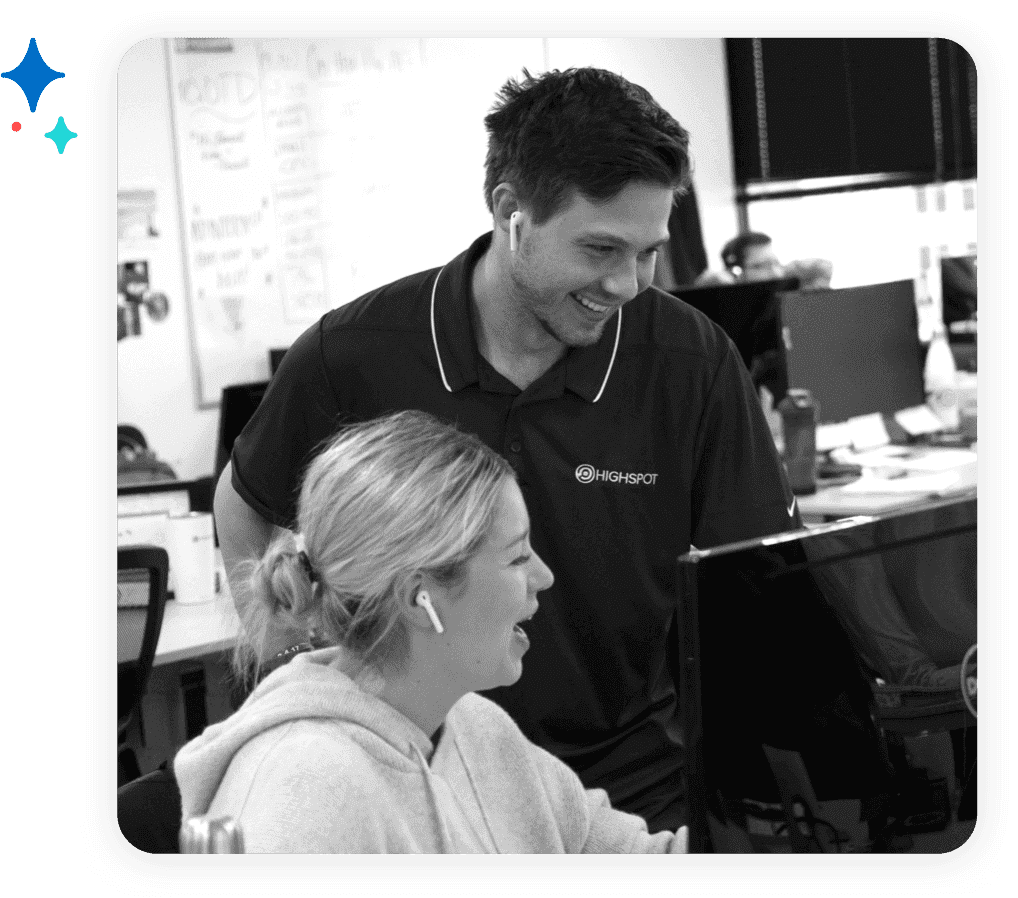

Make an Impact

At Highspot, you’ll do more than just busy work. Instead, you’ll be right at the heart of projects that matter—collaborating across teams and developing valuable skills to make a meaningful impact.

Our Interview Process

Step 1

Apply for

a Position

Step 2

Phone interview

with the recruiter

Step 3

Interview with the

manager

Step 4

Interview

with the team

Step 5

Get an

Offer!

After graduating from college a week before COVID closures, my original post-grad plans were put on hold forcing me to pivot to a new career path. The internship gave me the solid foundation necessary to strengthen my sales skills from cold calling to social selling, and I am forever grateful!

Sr. Account Development Representative

Account Development is the perfect way to kick start your career in tech sales. ADRs have the opportunity to grow into other areas of the business as this team is an integral part of our fast-growing People Engine. I love this team’s energy, tenacity, creativity, and genuine curiosity that takes prospecting to a whole new level.

Director, Account Development

The internship at Highspot was able to set me up for success because I was able to get familiar with the sales enablement space, learn best practices to personalize my outreach and get a sneak peak into the daily life of a sales enablement specialist.

Sr. Account Development Representative

Career Development and What We Offer

Accelerate Program

Highspot offers recent college grads, people early in their careers, and transitioning professionals a unique experience called Accelerate. With opportunities in our Account Development and Engineering teams, Accelerate provides tailored experiences that will jumpstart your career and catapult it to new heights at one of tech’s fastest-growing startups.

Internship Program

The Account Development Representative Internship Program (ADR Intern) gives unique exposure to our company, the technology industry and a sales career path. This opportunity is intended to develop and strengthen the necessary sales skills and technical knowledge including systems, tools and process to be successful in pursuing a career path as an Account Development Representative.