Sales Training Software

Mit einer einheitlichen Schulungsplattform werden Vertriebsmitarbeiter zu Superstars

Statten Sie Ihre Revenue Teams mit der innovativsten Schulungslösung aus.

Verstärktes Lernen für konsistente Quotenerfüllung

Setzen Vertriebsmitarbeiter neu erlerntes Wissen in die Praxis um? Führt Ihr Schulungsprogramm zu Änderungen im Verhalten? Wirkt es sich auf das Endergebnis aus?

Jetzt können Sie sich einen Überblick darüber verschaffen, wie sich die Kluft zwischen Theorie und Praxis auf die Ergebnisse auswirkt.

Die Schulung ist nur der erste Schritt. Mit Highspot können Ihre Sales Enablement- und Vertriebsteams KI nutzen, um wirkungsvolle Programme für Vertriebsschulung zu erstellen, die Vertriebsmitarbeiter zertifizieren, wichtige Fähigkeiten und Kompetenzen entwickeln und Teams aufbauen, die ihre Quoten übertreffen.

Verstärken Sie das Lernen über einen längeren Zeitraum, damit die Fähigkeiten erhalten bleiben und angewendet werden. Kontinuierliche Verstärkung steigert das Selbstvertrauen der Vertriebsmitarbeiter, ihre Sales Readiness und Vertriebsleistung. So können Sie Ihren Umsatz steigern und ein Vertriebsteam aufbauen, das Spitzenleistungen erbringt.

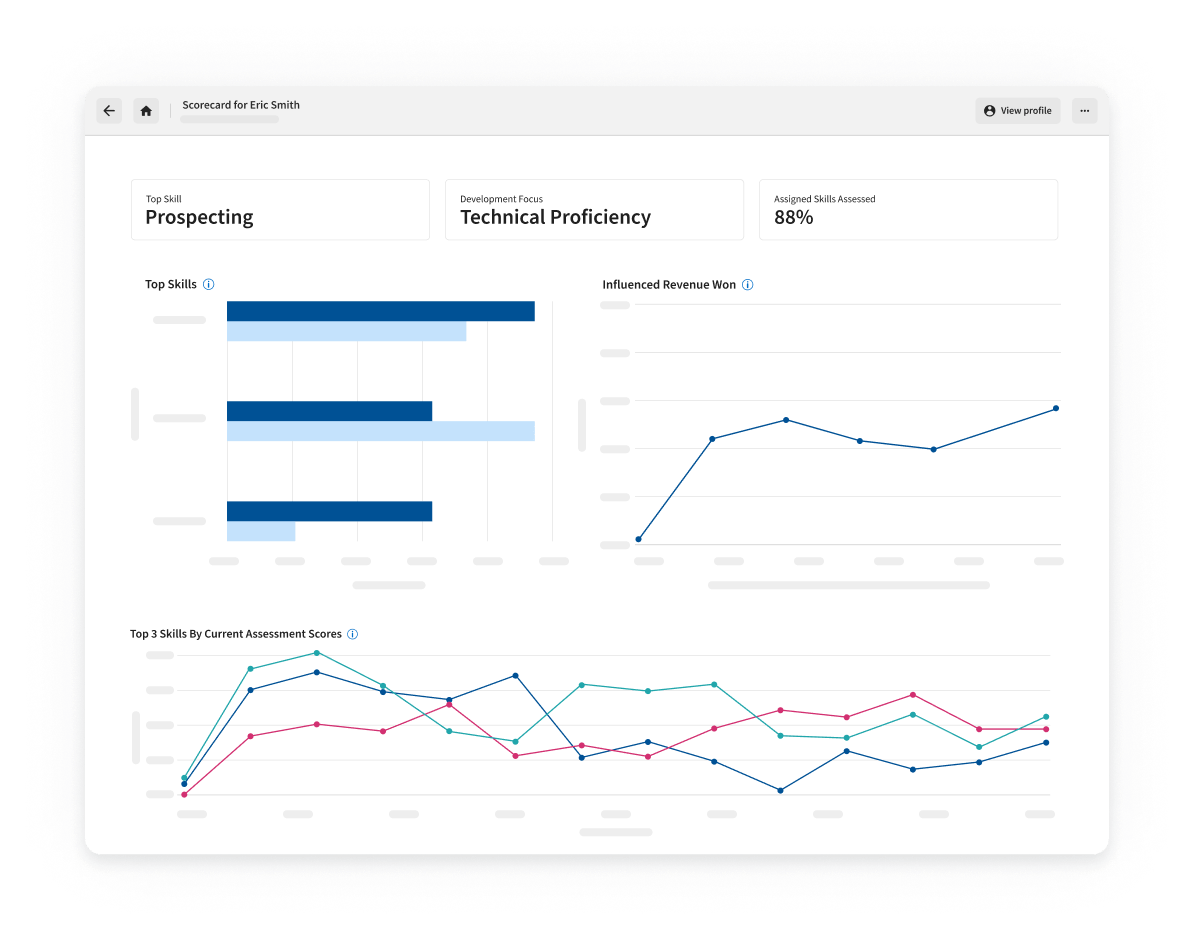

Mehr Umsatzwachstum mit datengestütztem Vertriebstraining

Befähigen Sie Teammitglieder mit einer Vertriebstrainingssoftware für mehr Umsatzwachstum. Die Highspot-Plattform nutzt KI-gesteuerte Schulungen und fortschrittliche Analytik, um Vertriebsleistung, Anlaufzeiten und Konversionsraten zu verbessern. So sehen Sie, wie personalisierte Schulungen zu Sales Readiness und Geschäftserfolg beitragen.

Schulungen mit KI personalisieren

Die Highspot-Plattform integriert Schulungskurse, Lernen vor Ort und Praxisübungen in Lernpfade. KI-Funktionen (z. B. Wissenstests) bieten Mitarbeitern Schulungen auf Abruf und sofortiges Feedback.

Vertriebsfähigkeiten in der Praxis validieren

Vertriebsleiter können aufgezeichnete Verkaufsgespräche überprüfen und erkennen, wie die Theorie in die Praxis umgesetzt wird. Nutzen Sie die intelligente Gesprächsführung, um Fähigkeiten zu bewerten.

Geschäftserfolg mit datengestützten Schulungen steigern

Verknüpfen Sie Schulungen schnell mit wichtigen Geschäftsmetriken wie Umsatzwachstum und Gewinnraten. Nutzen Sie Scorecards und Dashboards zur Analyse, Nachverfolgung und Entscheidungsfindung.

Sales Readiness mit personalisierten, KI-gestützten Schulungen beschleunigen

Schnelleres und effektiveres Onboarding Ihrer Teams mit KI-gestützter, personalisierter Vertriebsschulung. Mit Highspot entwickelt jeder Vertriebsmitarbeiter die für den Vertriebserfolg erforderlichen Fähigkeiten, verkürzt seine Einarbeitungszeit und trägt so zu konsitentem Vertriebserfolg bei.

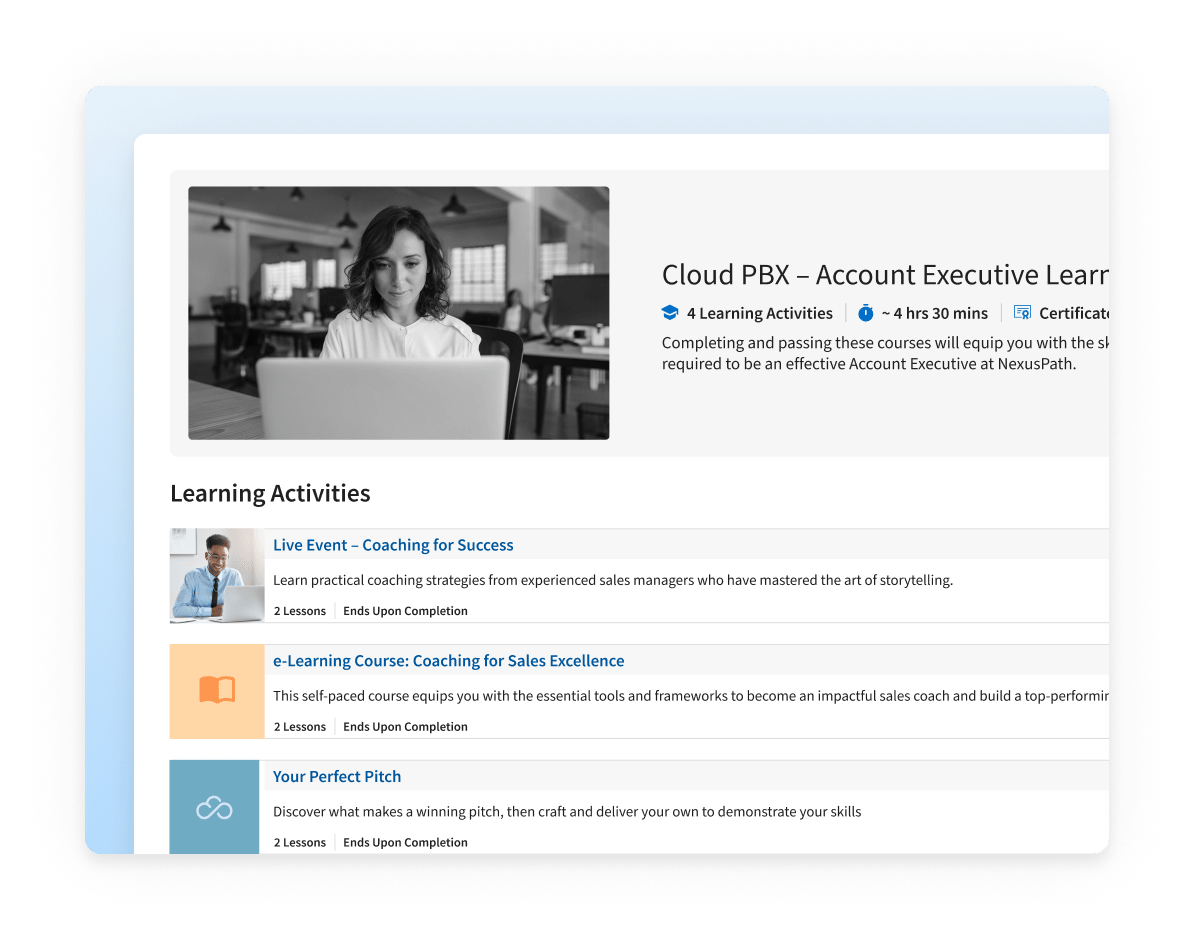

Individuelle Lernerfahrungen bereitstellen

Integrieren Sie Kurse, Lernen vor Ort und Praxisübungen in einen Pfad für alle Lernstile. Steigern Sie die Wissensbewahrung mit Zertifizierungen und importieren Sie externe Schulungen mit SCORM.

Mit Vorverkaufsübungen Vertrauen aufbauen

Bereiten Sie Vertriebsmitarbeiter mit Videoanalysen und Rollenspielsimulationen in Highspot auf Kundeninteraktionen vor und nutzen Sie KI-generiertes Feedback zur Bewertung von Darbietung und Inhalt.

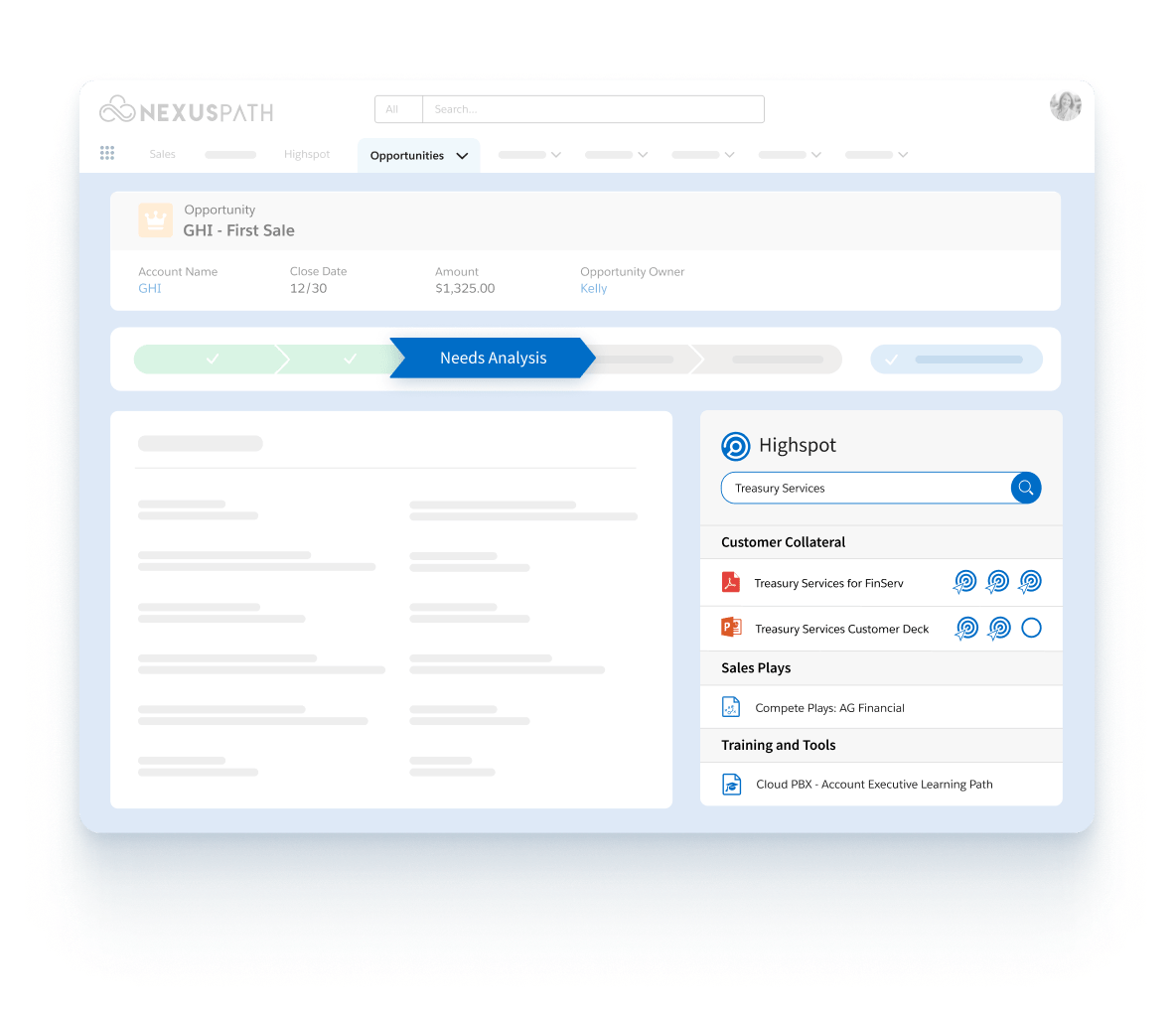

Richtige Kenntnisse und Vertriebsfähigkeiten zur richtigen Zeit

Verkaufsgespräche in der realen Welt entscheiden über den Erfolg des Vertriebsprozesses. Daher stellt Highspot entsprechende Schulungsmaterialien, Microlearning-Inhalte und Inhalte auf Abruf bereit.

Ihre Go-to-Market-Strategie mit einer nahtlosen Sales Enablement Experience vereinen

Einheitliche Schulungen, Coaching, Inhalte und Analytik an einem Ort bieten eine nahtlose Experience, die Ihre GTM-Strategie optimiert. Mit der Software von Highspot können Teams ihre Verkaufsfähigkeiten verstärken und ihren Erfolg steigern. Erzielen Sie datengestützte Ergebnisse, die den Umsatz und die Vertriebsleistung steigern.

GTM-Maßnahmen mit einer einheitlichen Plattform optimieren

Die einheitliche Highspot-Plattform verbindet Inhalte, Schulungen, Coaching und Analytik in einem nahtlosen System und vermeidet so Silos, um das Umsatzwachstum und die Betriebseffizienz zu steigern.

Lernen mit CRM-Integration verstärken

Verstärken Sie wichtiges Wissen mit CRM- und Meeting-Integrationen. Verbinden Sie z. B. Zoom, Cisco Webex und mehr und zeigen Sie Schulungen und Inhalte in Salesforce und Microsoft Dynamics 365 an.

Mehr Erfolg mit Highspot Marketplace-Partnern

Nutzen Sie den Highspot Marketplace für den Direktzugriff auf Top-Vertriebsinhalte, Schulungen und Best Practices, um Investitionen in die Verkaufsmethodik zu maximieren und Konsistenz zu fördern.

Nahtlose Integration mit all Ihren bevorzugten Tools

Erweitern Sie Ihren Technologie-Stackwert. Integrieren Sie Sales Enablement im Workflow der Vertriebsmitarbeiter mit Highspots Ökosystem von 100+ Integrationen.

Diese könnten Sie interessieren:

Vertriebsschulung der Weltklasse auf Abruf

- KI-generierte Mini-Quizze zu jedem Sales Playbook oder Inhaltselement

- Rubriken für Fertigkeiten, die von generativer KI bewertet werden

- Personalisierte Lernpfade, die Lernen vor Ort, Videoübungen und eLearning kombinieren

- Schnelle Erstellung von Lektionen und Kursen mit vorgefertigten Lektionsvorlagen

- Mehr als 30 Integrationen von Verkaufsmethodik-Partnern über den Highspot-Marktplatz

- Von Schulungsleitern durchgeführte Schulungen (ILT), von Schulungsleitern durchgeführte virtuelle Schulungen (vILT), Integration von Webkonferenzen und Anwesenheitsverfolgung

- Individualisierbare Zertifikate und Zertifizierungsausweise

- Kompetenzlücken mit aufgezeichneten Verkaufsgesprächen, Lerneinblicken und kuratierten Dashboards identifizieren

Um ihre Vertriebsziele zu erreichen, müssen Vertriebsmitarbeiter von ihrer Fähigkeit überzeugt sein, Geschäfte abzuschließen. Eine wirksame Vertriebsschulung bedeutet, dass Mitarbeiter mit Vertriebstechniken ausgestattet werden und das Verkaufswissen in die Praxis umgesetzt wird.

Vertriebstraining ist ein Schlüsselelement von Sales Enablement. Enablement- und Vertriebsfachleute benötigen eine Lernplattform, die sie bei der Einbindung neuer Mitarbeiter und der Erstellung von Schulungsprogrammen unterstützt. Vertriebsleiter können so die Auswirkungen der Schulungen auf den ROI in Echtzeit messen.

Sales Enablement zielt darauf ab, den Vertrieb zu skalieren, indem Verhalten und Vorgehensweisen der leistungsstärksten Vertriebsmitarbeiter auf das gesamte Team übertragen werden. Die meisten Marketing-, Enablement- und Vertriebsteams arbeiten jedoch mit unzusammenhängenden Systemen, die nicht die gewünschten Ergebnisse liefern. Highspot ist die einzige Plattform, die Ausstattung, Schulung und Coaching von Vertriebsmitarbeitern auf Erfolgskurs bringt. Sie hilft Ihnen, die Vertriebsproduktivität zu verbessern, den Umsatz konsistent zu steigern und das volle Potenzial Ihres Unternehmens auszuschöpfen. Mit dem einheitlichen Schulungsansatz von Highspot sorgen Sie dafür, dass jeder Vertriebsmitarbeiter mit den richtigen Fähigkeiten und Kenntnissen ausgestattet ist und in jeder Phase des Verkaufszyklus über die richtigen Inhalte zur richtigen Zeit verfügt, was schließlich zu vorhersehbaren Ergebnissen und nachhaltigem Wachstum führt.