Sales Enablement und Datenschutz

Sicherheit und DSGVO auf Ihrer Sales Enablement-Plattform

Wir bieten die Sicherheit, damit Sie entspannt verkaufen können.

Enablement-Initiativen modernisieren und Risiken minimieren

Passen Sie Ihre Sicherheits- und Compliance-Einstellungen einfach an Ihre Unternehmensanforderungen an. Von einzelnen Inhalten bis hin zur gesamten Plattform ist alles möglich.

Ihre Inhalte schützen

Schutz und Vertraulichkeit sind garantiert. Ihre Daten sind im Ruhezustand und bei der Übertragung verschlüsselt, um den Industriestandards und Ihren eigenen Sicherheitsanforderungen zu entsprechen.

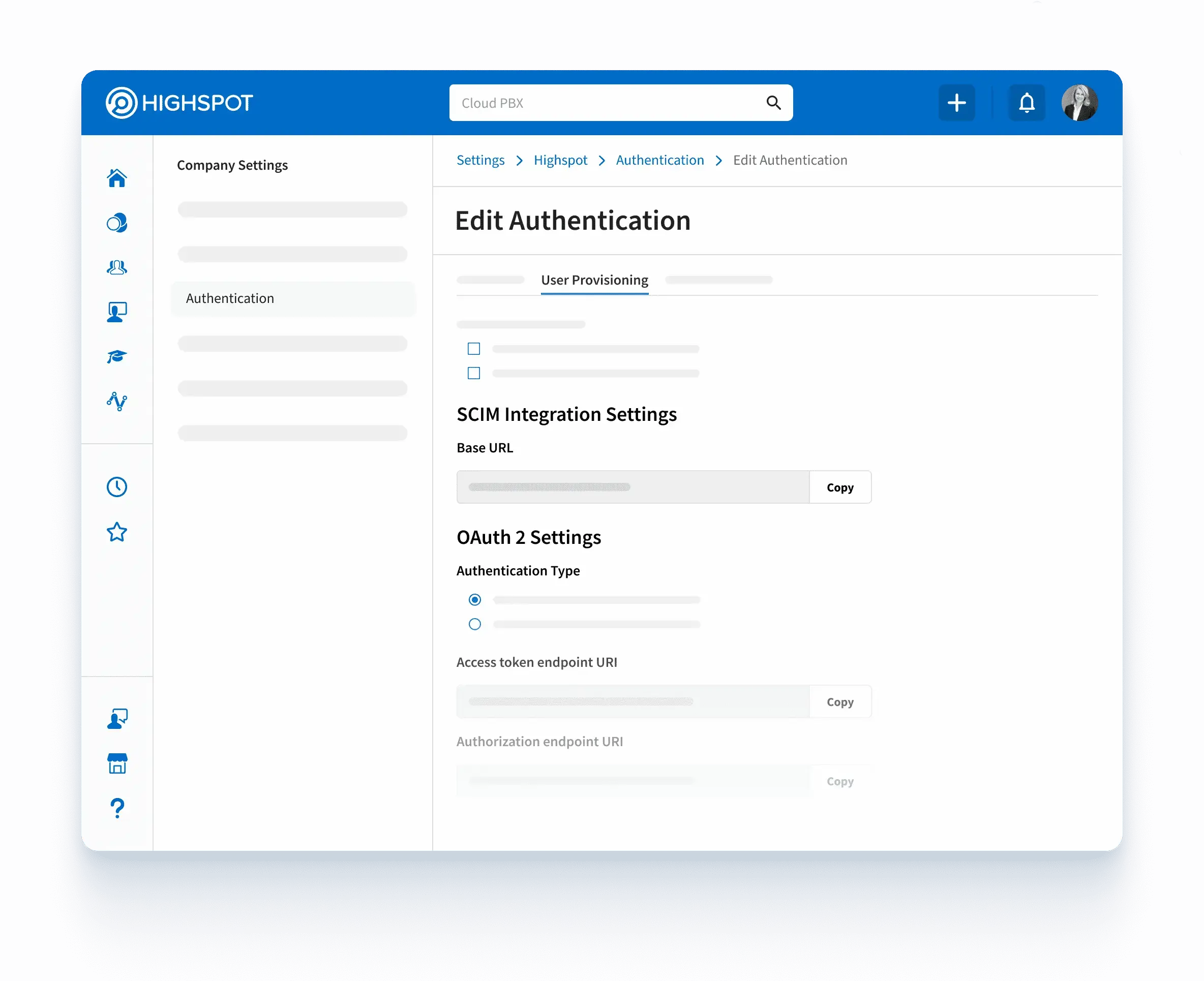

Ihre Sicherheitslösung personalisieren

Konfigurieren Sie die Sicherheit in Ihrem gesamten Highspot-Ökosystem, um den Zugriff zu verwalten, Risiken zu minimieren und sensible Daten zu schützen.

Ihren Datenschutz aufrechterhalten

Integrierte Datenschutzmaßnahmen ermöglichen es, sich auf Enablement-Maßnahmen zu konzentrieren und gleichzeitig sicherzustellen, dass Ihr Unternehmen die strengsten Datenschutzbestimmungen einhält.

Sicherheit durch einsatzbereite Systeme und anpassbare Kontrollen

Vereinfachung des Datenschutzes

Durch das einfache Hochladen von Inhalten in Highspot werden Ihre Daten im Ruhezustand und während der Übertragung verschlüsselt.

Erleichterungen für das Vertriebspersonal

Sofort einsatzbereite Funktionen und Automatisierungen ermöglichen es den Vertriebsmitarbeitern, Ihre Sicherheitsstrategie einfach umzusetzen.

Support für Datenschutz-Compliance

Erfüllen Sie lokale Vorschriften wie die DSGVO oder den CCPA, indem Sie die auf Datenschutzprinzipien basierenden Funktionen von Highspot nutzen.