Der Aufbau der Vertriebsorganisation ist nicht nur eine Frage der Unternehmens- und Vertriebsstrategie, sondern sollte jeden Vertriebsmitarbeiter in die Lage versetzen, sein Potenzial zu entfalten.

Viele Faktoren sind entscheidend, um ein leistungsfähiges Vertriebsteams aufzubauen. Lassen Sie uns hier die folgenden Aspekte behandeln:

- Was versteht man unter einer Organisationsstruktur für den Vertrieb?

- Auf welche Aufgaben sollte sich das Vertriebsteam konzentrieren?

- Welche Arten der Vertriebsorganisation gibt es?

- Wie strukturiert man ein Vertriebsteam?

- Was versteht man unter einem Sales Enablement Team?

- Was sind die Aufgaben eines Sales Enablement Teams?

- How do you organise your sales enablement team?

- Best Practices für den Aufbau leistungsstarker Vertriebsteams

Was versteht man unter einer Organisationsstruktur für den Vertrieb?

Die Struktur der Vertriebsorganisation bezieht sich zunächst auf den Aufbau Ihres Vertriebsteams in bestimmte Bereiche und Gruppen. Wie Sie Ihr Vertriebsteam organisieren, richtet sich nach den Regionen, die Sie bedienen, den Produkten und Dienstleistungen, die Sie anbieten, der Größe Ihres Vertriebsteams und der Dimension und Branche Ihrer Kunden.

Die Struktur der Vertriebsorganisation ist deshalb von Bedeutung, weil sie Ihre Vertriebsmitarbeiter in die optimale Ausgangsposition bringt, um erfolgreich agieren zu können. So würden Sie einem neuen, noch recht junioren Mitarbeiter nicht die Verantwortung für Ihre Großkunden übertragen. Ebenso wäre es wenig erfolgversprechend, einen auf dem Gesundheitssektor erfahrenen Vertriebsmitarbeiter für den Vertrieb in der Technologiebranche einzusetzen. Durch die wohlüberlegte Gestaltung Ihrer Vertriebsorganisation können Sie individuelle Fähigkeiten und Erfahrungen optimal nutzen und somit sicherstellen, dass die richtigen Vertriebler den richtigen Kunden zugeordnet werden.

Auf welche Aufgaben sollte sich das Vertriebsteam konzentrieren?

Natürlich ist Ihre Vertriebsorganisation dafür verantwortlich, Umsätze für Ihr Unternehmen zu generieren, indem sie Kunden zum Kauf eines Produktes oder einer Dienstleistung bewegt. Damit Ihre Vertriebsmitarbeiter einen Kauf erfolgreich abschließen können, müssen sie sich auf verkaufskritische Tätigkeiten konzentrieren. Die meisten Vertriebler geben allerdings an, dass sie häufig mit Tätigkeiten beschäftigt sind, die eher mit Sales Operations oder Sales Enablement zu tun haben. Oftmals nehmen administrative Aufgaben zu viel Zeit in Anspruch.

Meist lässt sich das auf Budget-Engpässe oder mangelndes Verständnis für die wirklichen Aufgaben eines Vertriebsmitarbeiters zurückführen – sprich, es fehlt an klaren Abgrenzungen zu anderen Vertriebsfunktionen, und damit an Support für das Kern-Vertriebsteam.

In der folgenden Tabelle sind drei wichtige Aufgaben der einzelnen Rollen kurz zusammengefasst:

| VERTRIEB | SALES OPERATIONS | SALES ENABLEMENT |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Vertriebsteams brauchen die Unterstützung von Rollen wie Sales Operations und Sales Enablement, um ihren eigentlichen Job erfolgreich machen zu können. Insbesondere das Sales Enablement nimmt in vielen Unternehmen einen immer größeren Stellenwert ein, wir gehen im Laufe des Artikels deshalb noch näher auf diesen Bereich ein.

Welche Arten der Vertriebsorganisation gibt es?

Es gibt drei grundlegende Modelle für Vertriebsteams: das Fließband-Modell, das Gruppen-Modell und das Insel-Modell. Jede dieser Strukturen hat ihre Vor- und Nachteile.

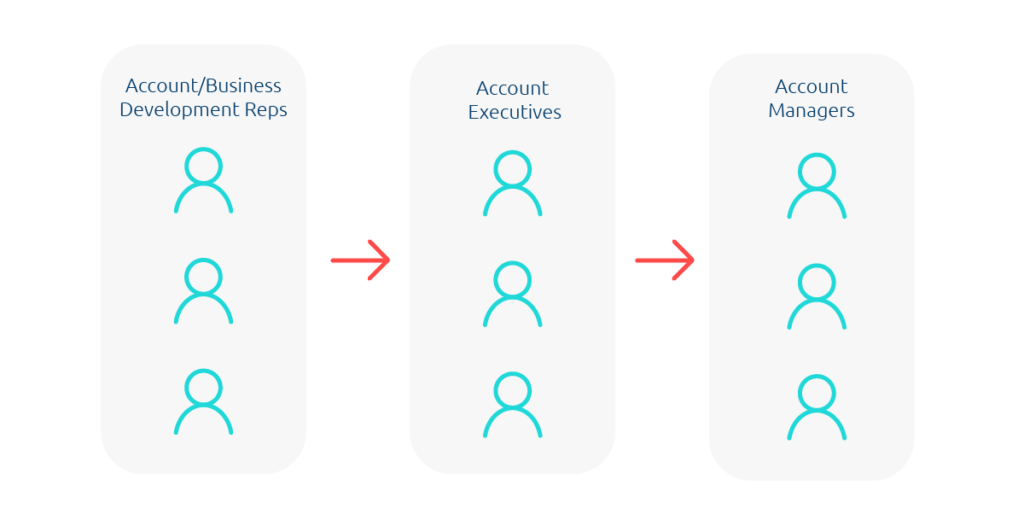

Hunter-Farmer-Modell: Der Fließband-Ansatz

Leads werden unter spezialisierten Teams weitergegeben

Beim Fließband-Modell – auch bekannt unter dem Begriff Hunter-Farmer-Modell – werden Vertriebsteams auf Grundlage ihrer jeweiligen Rollen organisiert. Die Bezeichnung rührt von der Ähnlichkeit mit einem Fließband in der industriellen Fertigung: In beiden Fällen führen spezialisierte Personen eine spezifische Aufgabe durch – beim Vertrieb besteht diese Aufgabe in der Begleitung der Käufer auf einem bestimmten Teil der Customer Journey.

Business Development Reps generieren eine Vertriebspipeline oder pflegen qualifizierte Leads. Die Leads werden dann einem Account Executive in der Kundenbetreuung übergegeben, der den Verkauf abschließt. Im Anschluss an den Verkaufsabschluss werden die Kunden an einen Customer Success Manager oder Account Manager weitergegeben, der die Kundenbeziehung für die Dauer des Kundenlebenszyklus aufrechterhält.

| VORTEILE | NACHTEILE |

|---|---|

|

|

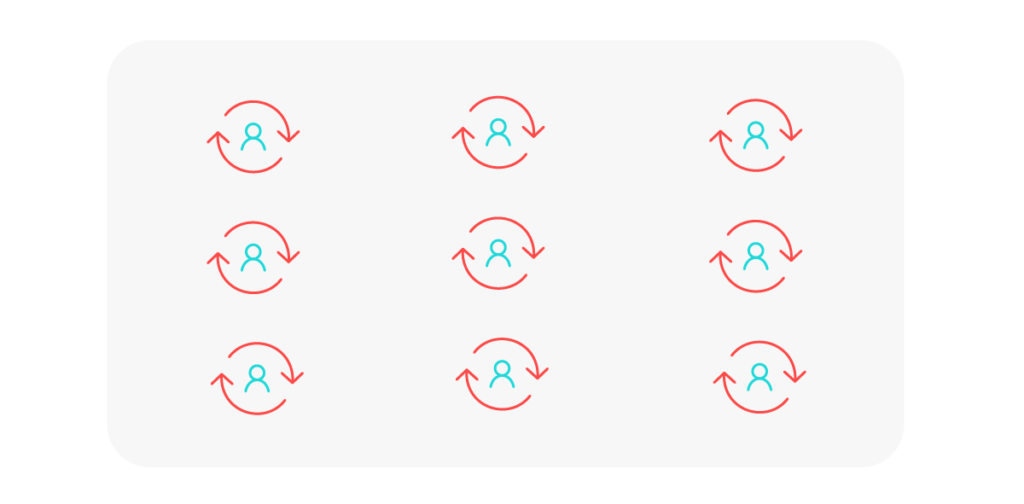

The Island: Das Insel-Modell

Vertriebsmitarbeiter betreut Kunden entlang der gesamten Customer Journey

Beim Insel-Modell ist jeder Vertriebler ein Allrounder: Ein einziger Mitarbeiter trägt die Gesamtverantwortung für den jeweiligen Kunden, von der Neukundenansprache bis hin zum Onboarding. Das bedeutet, dass ein Mitarbeiter Leads eigenständig generiert, qualifiziert und abschließt. Diese Methode ermöglicht den Mitarbeitern zwar ein hohes Maß an Eigenverantwortung beim Auf- und Ausbau von Kundenbeziehungen, sie setzt sie aber auch unter großen Druck. Für manche Unternehmen ist dies ein Vorteil, denn es schafft eine äußerst wettbewerbsorientierte Vertriebskultur.

Aufgrund seiner Einfachheit und dem Schwerpunkt auf dem Erfolg des Einzelnen wird das Insel-Modell oftmals von Unternehmen mit eher kleinen Vertriebsteams eingesetzt, die auf einen höheren Ertrag pro Mitarbeiter setzen oder bei denen die persönliche Kundenbetreuung einen hohen Stellenwert besitzt, wie etwa in der Finanzdienstleistungsbranche.

| VORTEILE | NACHTEILE |

|---|---|

|

|

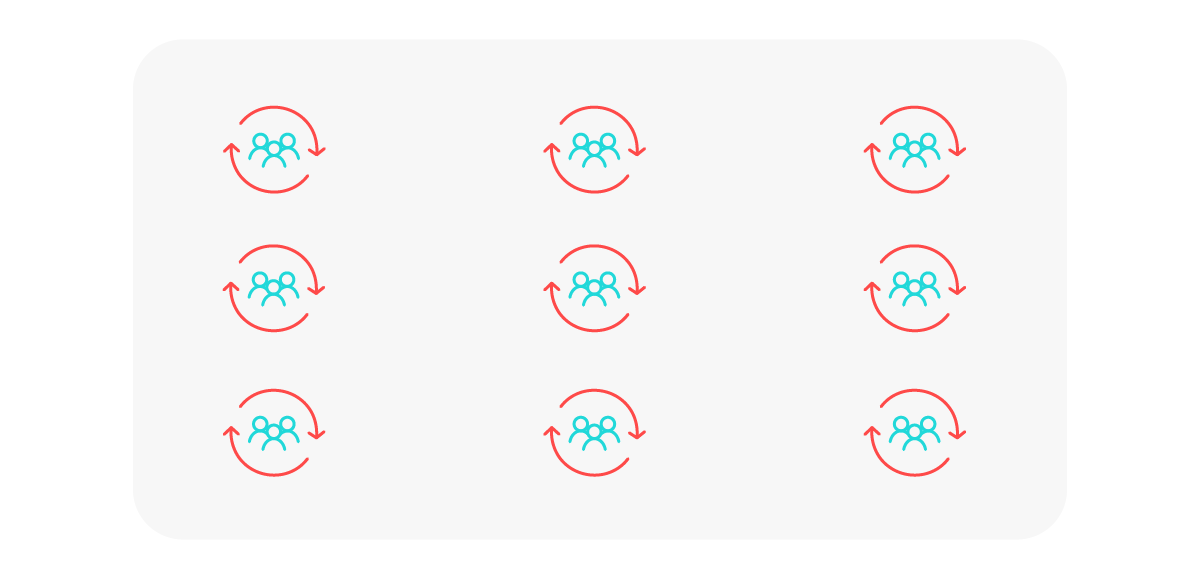

The Pod: Das Gruppen-Modell

Kleine Teams aus spezialisierten Vertriebsmitarbeitern betreuen Interessenten auf der gesamten Customer Journey

Dieses Modell kombiniert einzelne Elemente des Fließband-Modells mit Elementen des Insel-Modells. Wie beim Insel-Modell steht dem Kunden von der Neukundenansprache bis hin zum Onboarding eine einzige Gruppe zur Seite. Doch analog zum Fließband-Modell sind einzelne Mitarbeiter innerhalb dieser Gruppen auf spezifische Phasen der Customer Journey spezialisiert. Teil der Gruppe sind etwa ein Mitarbeiter im Bereich Kundengewinnung oder Geschäftsentwicklung, ein Account Executive und ein Customer Success Manager oder Account Manager

Das Gruppen-Modell ist bei größeren Unternehmen beliebt, die sich eine unkomplizierte Gliederung ihrer Vertriebsteams wünschen. Denn auf diese Weise kann die Vertriebsverantwortung für bestimmte Produktlinien, geografische Gebiete oder Branchen je nach Bedarf leicht einzelnen Gruppen zugewiesen oder neu delegiert werden. Das Gruppen-Modell ist auch für den kundenbasierten Vertrieb gut geeignet, denn eine einzige Gruppe kann einen Zielkunden wirksam anwerben.

| VORTEILE | NACHTEILE |

|---|---|

|

|

Weitere Merkmale der Modelle

Sie können Ihre Vertriebsteams auch nach zusätzlichen Faktoren gliedern, wie zum Beispiel nach:

- Geografische Region/Gebiet

- Produkt/Dienstleistungsangebot

- Kundengröße

- Branchenspezifische Kundensegmentierung

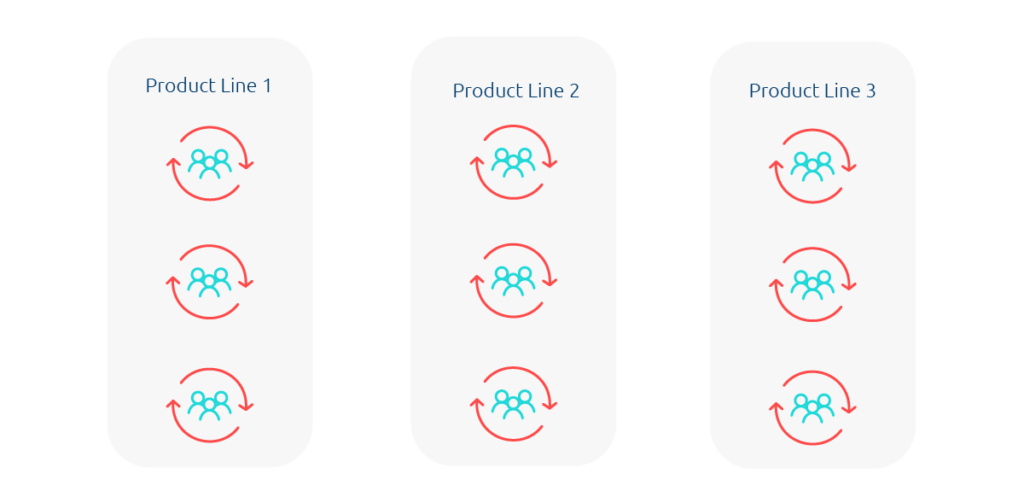

Die Faktoren können mit jedem der beschriebenen Modelle kombiniert werden. Ein Unternehmen, welches das Fließband-Modell nutzt, kann diese Struktur beispielsweise für jede geografische Region, in der es tätig ist, replizieren. Oder ein Unternehmen, welches nach dem Pod-Modell arbeitet, kann eine Produktlinie einer spezifischen Gruppe zuorden.

Beispiel des Pod-Modells, segmentiert nach Produktlinie

Mit zunehmendem Wachstum eines Unternehmens sind in der Regel zusätzliche Strukturen erforderlich, zum Beispiel um spezifische Märkte zu bedienen.

Wie strukturiert man ein Vertriebsteam?

Bei der Suche nach der richtigen Struktur für Ihr Vertriebsteam sind eine Reihe von Faktoren zu beachten. Machen Sie sich zunächst Gedanken über:

- Ihr Budget: Ein höheres Budget ermöglicht die Investition in ein größeres, spezialisierteres Vertriebsmodell, wie z. B. das Gruppen- oder Fließband-Modell. Kleinere Unternehmen erzielen unter Umständen mit dem Insel-Modell den höchsten Umsatz pro Mitarbeiter.

- Ihre Kunden: Wo Ihre Kunden ihren Sitz haben, welche Produkte sie in der Hauptsache kaufen und wie groß sie sind, sind Anhaltspunkte, anhand derer Sie nicht nur Ihr Vertriebsmodell bestimmen, sondern auch festlegen können, wie stark dieses gegliedert sein muss, um erfolgreich zu sein.

- Ihre Kultur: Jedem Vertriebsmodell wohnt eine eigene Kultur inne – denken Sie darüber nach, ob eine kollaborative Teamstruktur besser mit Ihren Unternehmenswerten vereinbar ist oder ob Sie mehr Wettbewerb innerhalb des Vertriebsteams vorziehen.

Was für das eine Unternehmen funktioniert, muss für Ihres nicht zwangsläufig auch das Richtige sein. Entscheidend ist, das richtige Modell für Ihr Unternehmen zu finden – bedenken Sie dabei auch, dass Sie möglicherweise auf ein anderes Modell umschwenken müssen, wenn Ihr Vertriebsteam wächst.

Abschließend ist es wichtig zu berücksichtigen, dass Ihr Vertriebsteam nicht im luftleeren Raum existiert. Ihre Vertriebsstruktur wird auch von unterstützenden Funktionen wie Sales Enablement und Sales Operations beeinflusst – und umgekehrt. Überlegen Sie, welche Erwartungen Sie hinsichtlich der Arbeit dieser wichtigen Funktionen innerhalb Ihres Vertriebsmodells haben – und wie Sie sie strukturieren werden, um sicherzustellen, dass sie ebenso effektiv agieren.

Was versteht man unter einem Sales Enablement Team?

Im Kern versteht man unter Sales Enablement sämtliche Aktivitäten, die den Vertrieb mit den Tools, Skills und Inhalten ausstatten, die er braucht, um mit (potenziellen) Kunden zu interagieren und Umsatz zu erzielen.

Im Zuge der wachsenden Komplexität moderner Verkaufszyklen und dem zunehmenden Informationsgrad der Kunden gewinnt dieser Punkt immer mehr an Bedeutung. Früher musste sich der Kunde darauf verlassen, dass ihn der Vertriebler über das Produktangebot informiert – heute interagiert der Kunde mit dem Vertriebler erst dann, nachdem er selbst gründlich recherchiert hat. In dieser neuen Welt erwarten Käufer von Vertriebsmitarbeitern tiefe Einblicke und Orientierung, und einen Mehrwert der Informationen, die ihnen der Vertriebler bietet. Er muss nicht als Verkäufer, sondern als „Trusted Advisor“ agieren können.

Unternehmen investieren daher zunehmend in das Sales Enablement, um ihre Vertriebsteams für genau diese Situation fit zu machen, und die Erwartungen der Käufer voll und ganz zu erfüllen.

Was sind die Aufgaben eines Sales Enablement Teams?

Ein Sales Enablement Team erfüllt seine Mission – nämlich die Steigerung der Vertriebseffektivität – indem sie sich auf folgende Schwerpunkte konzentriert:

- Training und Onboarding

- Content und Guidelines

- Analyse und Business Intelligence

Training und Onboarding sorgen dafür, dass die Vertriebler über das nötige fachliche und inhaltliche Know-How verfügen, um ein Kundengespräch erfolgreich führen zu können. Dieser kontinuierliche Lernprozess beginnt für den Mitarbeiter bereits am Tag seiner Einstellung – und sollte, mit Unterstützung eines Sales Enablement Teams (und der richtigen Sales Enablement Plattform), Teil seiner täglichen Arbeit werden. Sales Enablement Teams können das leisten, indem sie den Onboarding-Prozess neuer Mitarbeiter steuern, Trainings- und Coaching-Aktivitäten koordinieren und Micro-Learning in ihre Sales Enablement Plattform integrieren.

Content und Guidelines bezieht sich auf den Prozess der Erstellung und Bereitstellung von Vertriebsinhalten und Unterlagen. Content spielt eine entscheidende Rolle sowohl bei der Ansprache des Kunden als auch beim Abschluss des Geschäfts, doch oftmals investieren Unternehmen nicht hinreichend in diesen Bereich. Es wird umfangreicher Marketing- und Sales- Content erstellt und dann einfach auf Laufwerken abgelegt – doch klassische Ablagesysteme oder Content Management Tools sind schlichtweg nicht dafür gemacht, die aktive Nutzung zu forcieren. Enablement Teams können die Effektivität von Content Assets maximieren, indem sie für bessere Auffindbarkeit sorgen und zudem Guidelines darüber geben, wie die Content Assets im Laufe des Vertriebszyklus am besten eingesetzt werden können.

Analyse und Business-Intelligence stehen im Zentrum der Erfolgsoptimierung eines Vertriebsteams. Tiefgehende Analyse und Business Intelligence im Zusammenhang mit der Nutzung von Inhalten, der (Nicht-) Inanspruchnahme von Trainings oder dem Erfolg (bzw. Misserfolg) einer bestimmten Verkaufstechnik ermöglichen den Vertriebsteams strategische Entscheidungen darüber, wie sie ihre Stärken nutzen und ihre Schwachpunkte kompensieren können. Durch das Tracking und Monitoring dieser Daten leisten Sales Enablement Teams einen wichtigen Beitrag zur kontinuierlichen Verbesserung ihrer Vertriebsorganisation.

Wie organisiert man ein Sales Enablement Team

Immer mehr Unternehmen erkennen die Bedeutung von Sales Enablement und planen, dezidierte Ressourcen und Budgets für diese Funktion bereitzustellen. Im Folgenden stellen wir einige Schlüsselrollen vor, die Sie für ein erfolgreiches Sales Enablement Team brauchen, und erläutern die Gründe dafür.

Chief Revenue Officer (CRO)

Der Chief Revenue Officer verantwortet in der Regel alle umsatzrelevanten Funktionen und Teams: Vertrieb, Sales Operations, Marketing und eben auch Sales Enablement. Die Rolle des CRO ist deshalb von Bedeutung, weil das Engagement der Geschäftsführung für den Erfolg des Sales Enablement absolut wichtig ist. Ohne entsprechende Visibilität auf Management-Ebene wird es schwierig, die Investition für das Sales Enablement zu rechtfertigen oder Programme effektiv umzusetzen.

Head of / Director Sales-Enablement

Der Director Sales-Enablement ist für Ihre Sales Enablement Strategie verantwortlich und steuert das Sales Enablement Team. Er agiert auch als Schnittstelle zu Vertrieb und Marketing, und arbeitet eng mit diesen Teams zusammen, um zu gewährleisten, dass die Sales Enablement Programme effektiv sind.

Sales Enablement Specialist

Sales Enablement Spezialisten übernehmen spezifische Aktivitäten Ihres Sales Enablement Programms, wie zum Beispiel die Erstellung von Sales Content oder die Pflege Ihrer Sales Enablement Plattform.

Selbstverständlich kann nicht jedes Unternehmen eine Sales Enablement Funktionen in diesem Umfang etablieren – betrachten Sie diese Rollen daher als Grundlage für eine langfristige Vision. Im ersten Schritt kann es schon ausreichend sein, eine einzige dedizierte Sales Enablement Resource zu benennen, die das Thema weiter vorantreibt und Sie beim langfristigen Aufbau des Teams und der Einführung notwendiger Tools unterstützt.

Best Practices für den Aufbau leistungsstarker Vertriebsteams

Die besten Organisationsmodelle können nicht wirksam sein, wenn es in der praktischen Umsetzung an wichtigen Aspekten scheitert.

Beginnen Sie mit dem Produkt

Wenn Sie sich Gedanken darüber machen, wir Sie Ihren Vertrieb am besten aufstellen, dann beginnen Sie mit einem Blick auf Ihr Produkt: Es bestimmt Ihren Vertriebsprozess und damit auch das Modell, das für Ihr Unternehmen erfolgversprechend ist.

Die Immobilien- oder Finanzbranche beispielsweise stützt sich stark auf die Beziehung zwischen Verkäufer und Kunde – daher ist ein Modell mit häufigen Übergabepunkten wenig geeignet, um eine dauerhafte Beziehung aufzubauen. Mit solchen Vorüberlegungen stellen Sie sicher, dass Sie planvoll und kundengerecht in den Markt einsteigen.

Einfachheit vor Komplexität

Viele Unternehmen operieren in komplexen Organisationen, auch weiteres Wachstum bedeutet perspektivisch oftmals eine Zunahme der Komplexität im Vertrieb. Es ist jedoch wichtig, dass Sie sich auf den derzeitigen Stand Ihres Vertriebsteams konzentrieren. Wie kann Ihre Struktur die gegenwärtige Arbeitsweise unterstützen?

Die Skalierbarkeit ist zwar wichtig, sollte aber keinen Vorrang vor aktuellen Anforderungen haben. Wenn die Zahl Ihrer Vertriebsmitarbeiter gering und Ihr Budget begrenzt ist, kann ein komplexes Modell die Performance Ihres Vertriebsteams sogar bremsen und Ihr Wachstum verlangsamen. Eine einfache Struktur bedeutet zudem größere Flexibilität, um sie an die Weiterentwicklung Ihrer Organisation anzupassen.

In Mitarbeiter investieren

Durch die Investition in Ihre Mitarbeiter können Sie sicher sein, dass diese sich mit der Veränderung ihrer Rollen und Aufgaben auch weiterentwickeln. Ihre Vertriebsorganisation wird sich mit der Zeit zwangsläufig neu organisieren – was bedeutet, dass Ihre Vertriebsmitarbeiter wahrscheinlich zunehmend spezialisierte Rollen ausfüllen müssen, die spezifische Fähigkeiten erfordern.

Bereiten Sie Ihre Vertriebsteams darauf vor, indem Sie einen Entwicklungsplan erstellen. Halten Sie darin fest, wie Sie sich die Weiterentwicklung Ihres Vertriebsteams und der einzelnen Mitarbeiter vorstellen und über welche Kernkompetenzen sie verfügen müssen, um erfolgreich zu sein.

Die umfangreiche Investition in das kontinuierliche Training und Coaching ist unumgänglich, damit Ihre Teams über das taktische Know-how verfügen, um auch in einer veränderten Vertriebsumgebung erfolgreich sein zu können.

Sales Enablement priorisieren

Mit einem strategischen Sales Enablement Ansatz geben Sie Ihren Vertriebsmitarbeitern die nötigen Tools und Fähigkeiten an die Hand, damit sie erfolgreich sein können. Eine Sales Enablement Plattform hilft dabei, Sales Enablement Maßnahmen effektiv umzusetzen, zu skalieren und den Einfluss auf den Vertriebserfolg zu messen. Eine solche Plattform sollte deshalb neben effektivem Content Management auch die Möglichkeit tiefgehender Analysen bieten.

Kultur berücksichtigen

Vertrieb ist schwierig. Trotz oftmals frustrierender Kundenanforderungen und ständiger Zurückweisung arbeitet Ihr Vertriebsteam unermüdlich für den Erfolg Ihres Unternehmens. Aus diesem Grund ist die Kultur von so großer Bedeutung – sie fördert die Motivation und lässt Ihre Mitarbeiter ihr Bestes geben.

Eine Vertriebskultur kann wettbewerbsorientiert sein, aber trotzdem Werte wie Empathie und offene Kommunikation umfassen. Insbesondere Ihre Führungskräfte sollten diese Werte tagtäglich vorleben. Dadurch fühlen sich Ihre Mitarbeiter als Teil eines übergeordneten Teams, selbst wenn sie nach Regionen, in Gruppen oder auf sonstige Weise aufgeteilt werden.

Bereiten Sie Ihr Sales Team für den Erfolg vor

Erfahren Sie mehr über Vertriebserfolg in der neuen virtuellen Vertriebswelt in der aktuellen Studie von SiriusDecisions.